There are few images in modern film and literature more memorable than the central image of Life of Pi. The striking idea of a young boy stranded on a lifeboat with a Bengal Tiger is one that begs symbolic interpretation. Now, the question of religious faith is an obviously central part of the story with belief in this fantastical tale being associated with a religious “leap of faith” at the end. However, much of this story’s true thematic depth comes from an understanding of what is presented as the symbolic meaning of zoos.

The focus on zoos at the beginning of Life of Pi is no coincidence. The film adaptation begins with a beautiful montage of the zoo owned by Pi’s father, and the opening lines tell the story of Pi’s birth corresponding with an animal being killed outside the protective confines of the zoo. Pi learns quickly of the necessity of the zoo’s inherent structure.

The opening of the novel goes into even more detail about how Young Pi actually becomes an ardent defender of zoos. To those who may see zoos as unjust and restrictive of freedom, he argues,

“Well-meaning but misinformed people think animals in the wild are “happy” because they are “free.” The life of the wild animal is simple, noble and meaningful, they imagine. Then it is captured by wicked men and thrown into tiny jails…This is not the way it is.

He goes on to explain,

Animals are territorial. That is the key to their minds… In a zoo, we do for animals what we have done for ourselves with houses: we bring together in a small space what in the wild is spread out…A good zoo is a place of carefully worked-out coincidence; exactly where an animal says to us, “Stay out!” with its urine or other secretion, we say to it, “Stay in!” with our barriers. Under such conditions of diplomatic peace, all animals are content and we can relax and have a look at each other.”

The image of a zoo, therefore, becomes a symbol of the necessity of barriers and boundaries — of an ordered world designed to keep what is potentially harmful at bay. It’s a symbol that in many ways draws us to rethink the concept of freedom itself.

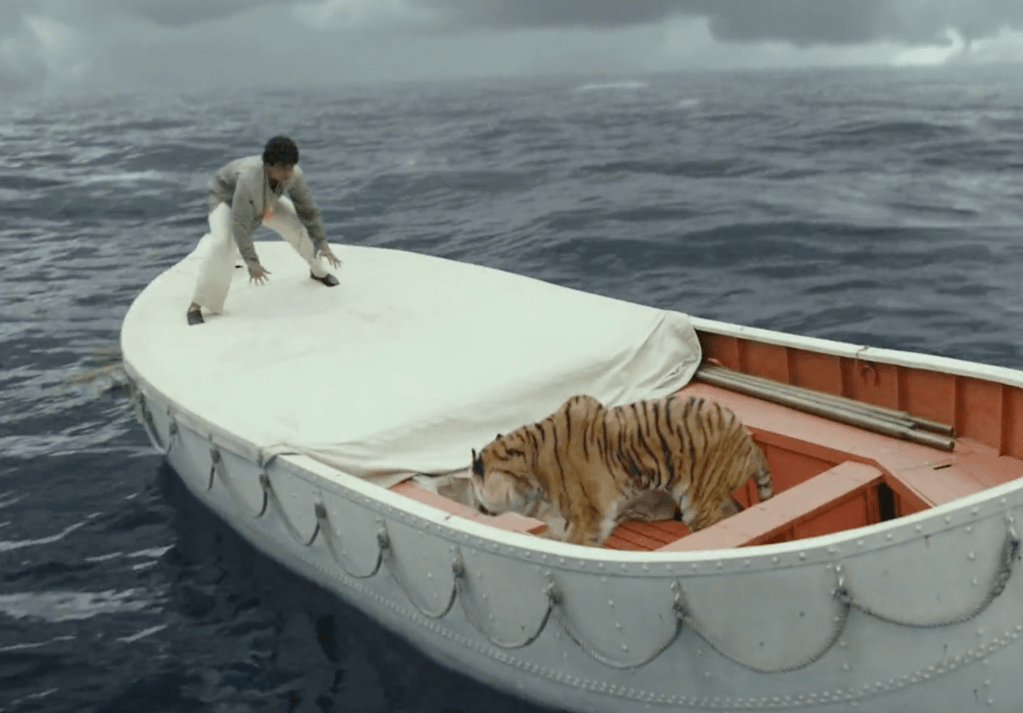

What we should not miss, then, is that once Pi is stranded on the lifeboat, the story actually revisits the motif and meaning of zoos. The ocean, a classic symbol of chaos and the unknown, surrounds Pi. At this point, we can view Pi as being completely outside of all boundaries. The lifeboat is essentially an inverted image of a zoo. Richard Parker, the Bengal Tiger, is chaos and malevolence embodied. He can devour Pi at whatever time he chooses.

So what does Pi do, when faced with such darkness and chaos? Does he hold onto a sense of “freedom” at all costs? On the contrary. In Pi’s wisdom, he manifests exactly what occurs in a zoo. He creates boundaries and limits. He establishes a hierarchy and tames the forces of chaos. Now, we can interpret the symbolism going on here on multiple levels.

The Lifeboat as the Jungian Self

In a psychological sense, we can view the tiger, Pi’s lone companion who emerges from the belly of the lifeboat, as representing a kind of internal darkness within Pi himself. He is the Jungian archetype of the shadow, his passions or vices, the forces of evil that he must face at the bottom of the abyss. Viewing things in this way calls to mind Carl Jung’s advice that we must confront our shadows and recognize our own darkness lurking within. Taming Richard Parker, then, suggests that Pi is properly ordering his internal life. Like all of us, he needs limits and boundaries to keep his tendency towards evil in check.

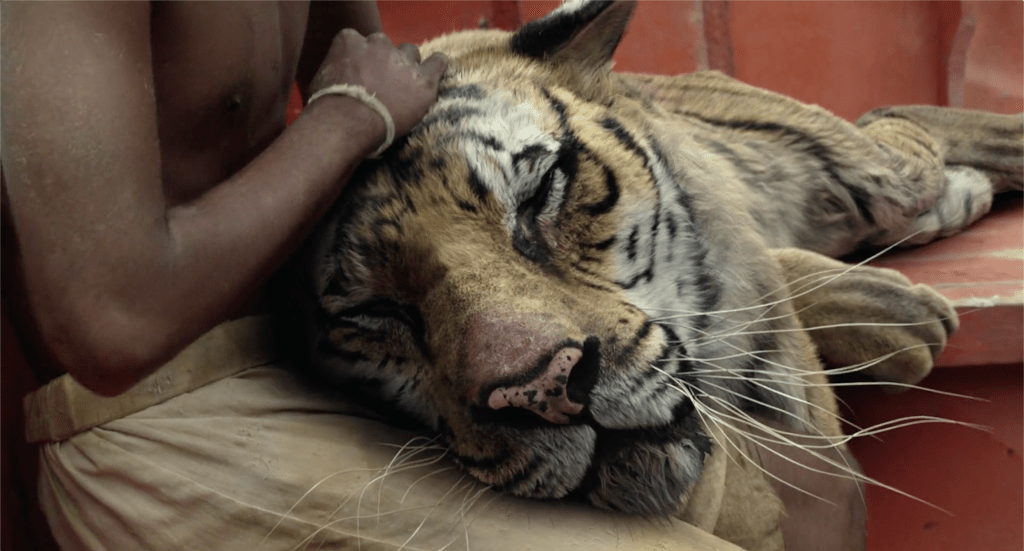

Once he is tamed and order is established, the once dark harbinger of death becomes Pi’s companion on his journey. In fact, Pi credits Richard Parker for saving his life. Due to his discipline and his vulnerability, we can view Pi as having attained a full sense of self during his journey. It is only after he has integrated his dark and animalistic impulses that he can endure his hardships.

We can see this interpretation play out as Pi is forced to kill in order to survive. On the lifeboat, he kills fish and turtles to feed himself and Richard Parker, going against his firmly held ideal of nonviolence. And part of the more “realistic” version of the story revealed at the end involves Pi taking the life of another sailor.

The Lifeboat as an Image of Reality

But there are broader symbolic ideas at play here as well. A good amount of time in the beginning of the story is spent exploring young Pi’s deep affection for religion and his attraction to elements from many different religions. And in the chapter dedicated to his defense of zoos, Pi actually connects his defense of both religion and zoos, with continued commentary on the ideas of boundaries and freedom. He states plainly,

“I know zoos are no longer in people’s good graces. Religion faces the same problem. Certain illusions about freedom plague them both.”

In the modern world, we are obsessed with freedom, with liberation. We tend to think that any rule, structure, or truth presented as absolute to be ultimately restricting. Life of Pi urges us to see through this shallow notion. According to Pi, a zoo — and a religion for that matter — may seem to some to repress freedom. But he still insists otherwise.

The structured world of a zoo (and therefore the lifeboat with clear barriers and a clear hierarchy) can be seen as the proper view of reality itself. Pi is offered a more transcendent sense of freedom because he submits to a certain level of order, which is another way of viewing Pi’s taming of Richard Parker. A life of boundaries — of limits and a transcendent structure — may be the only way to face life’s inevitable tragedies and the only way to flourish. What, after all, is a meaningful life if not a life of intention, of discipline, of self-chosen boundaries?

These themes are also reinforced when Pi and Richard Parker land on the mysterious island made of edible algae towards the end of their journey. It aimlessly floats across the ocean, without a structural foundation, offering brief respite and a facade of pleasure and comfort. It is a seemingly boundless world of ease, illusory freedom, and mindless consumers. But upon further inspection, its sinister and carnivorous nature is revealed, and Pi and Richard Parker choose to move on together.

So while the question of religious belief is central to Life of Pi, this symbolism that plays off the image of a zoo also encourages us to ask other important questions:

- What limits do we need in our lives to enjoy a greater sense of freedom?

- What boundaries do we need to establish in order to flourish?

- What are the “tigers” that we need to tame?

Leave a comment