“A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life.“

~Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder

The experiences of childhood and the minds of children have long been idealized. The poet William Wordsworth famously said that “The child is father of the man.”1 Jesus recognized their worth and unique perspective, welcoming children to his side.2

I recently had the chance to re-watch Disney’s 1953 version of Peter with my kids, and of course, its portrayal of these themes was very nostalgic. This story is beloved, but seeing it through new eyes, I couldn’t help feeling disappointed. Sure, there are some obvious reasons to feel this way these days. But I also found that way the film portrayed the notions of childhood and growing up to ultimately lacking.

I also couldn’t help comparing it to another animated film centered on childhood: Hayao Miyazaki’s groundbreaking film My Neighbor Totoro. Like Peter Pan, this film has many charming and memorable elements, but I would argue that My Neighbor Totoro succeeds thematically where Peter Pan falls short.

Here are two questions that I think are central to both of these films:

- What about childhood is worth retaining or rediscovering in adulthood?

- What does it mean to grow up?

So what does Peter Pan have to say about childhood that is worth retaining? We see the lives of the children in the film as imaginative, full of wonder and fantastical stories. Children hold onto high-minded ideals, and are fueled by a sense of adventure. Their whimsy and imagination allow them to live more fully in the present moment, without being dragged down by the drudgery of adult life. The character Peter Pan is the obviously representative archetype of all of these qualities.

In My Neighbor Totoro, we see many similar characteristics in its portrayal of the sisters, Satsuki and Mei. They are heartwarmingly innocent. They relish simple joys. In the same way that the children’s innocence and inherent optimism allows them to “fly” over the world of adults in Peter Pan, the perspective of the children in My Neighbor Totoro is also described as automatically insightful, since only the children can see the local spirits. It’s no surprise that Mei, the youngest and most innocent, is the best mediator between the spirit world and the real world. And in general, I think that Mei is one of the best portrayals of the spirit of childhood in any film.

One of my favorite aspects of the film’s portrayal of a treasured quality of childhood is that the children are inherently attracted and connected to nature — which, like most Miyasaki films, is closely linked to the spirit world. I think my favorite scene in this regard is the morning after the girl’s magical flight with Totoro. Despite experiencing the truly miraculous the night before, they still rejoice in what they also see as wonderful and miraculous the next day: the growth of new seedlings from Totoro’s seeds.

Where I see these two films truly diverging, though, is when we arrive at our second question: what does it mean to grow up?

In Peter Pan, the thought of growing up is immediately thrust into a negative light. More than that, it is described as an either-or scenario — once you “grow up” you can never go back. There is also no in-between stage. And once you are an adult, all of the wonders of childhood — the stories, the adventure, the light-hearted fun — must come to an end. I suppose the ending scene does hint at the possibility that Mr. Darling could rediscover some of what he had as a child. But overall, the choice seems two-sided: fly to Neverland or face the inevitable weight of the responsibility and the fussiness of adult life.

Now I love a lot in Peter Pan — the symbol of the ticking crocodile, the idea that Neverland is found in “happy thoughts,” and the character of the perpetually adolescent Peter Pan. But I think that a lot of the thematic depth missing is, in part, a sad case of the play and book being better than the movie. Take, for example, the play’s exploration of facing the inevitability of death as part of growing up, captured in one of its most famous lines, “To die would be an awfully big adventure.”3 This is completely left off in the animated version. Other factors involved in the growing up process explored in the book, such as the only briefly mentioned subject of motherhood in Wendy’s case, are just explored half-heartedly or not at all. For the most part, the film overemphasizes aesthetics, and seems to say primarily that growing up means no more fun.

I think My Neighbor Totoro, on the other hand, handles the question of growing up with much more nuance. At the beginning of the film, the family’s new house is emblematic of their new stage of life. The innocence and excitement of the sisters as they explore are contrasted with darkness and the decaying structures around them. Reminders of death are everywhere, and the house is even said to be haunted. Additionally, the subject of the children facing fear is present from the beginning of the story. Even Totoro himself has an initially frightening appearance.

This all makes sense when it is revealed that the mother of the family is potentially fatally ill. That she herself may be on the verge of decay. This is what truly marks their new stage of life. The film, then, seems to suggest that facing fears and embracing the harsh realities of life — including the inevitable death of our loved ones — is perhaps the most difficult part of what it means to shoulder the burden of maturity. Where the creators of Peter Pan shied away from this very subject, it is so impressive to me that My Neighbor Totoro is able to realistically present this theme, while still being fully accessible and beloved by children.

Like the film’s motif of a seed, a classic symbol for life coming out of death, the children are able to face these grim realities and fears, without losing their optimistic spirit. I think the film suggests that one can endure life’s tragedies and not completely lose one’s innocence. That we can face the dark and frightening, and embrace it, like a neighbor.

Another thing that I love about this film is that, unlike Peter Pan, it does not present the growing up process as a sudden all-or-nothing leap. The older sister Satsuki plays an important role in representing the phase of adolescence between childhood and adulthood. She is still curious, imaginative, and awed by nature, but she is slower to see the spirits. She is hit harder with heavier burdens of responsibility in her family. She must care for Mei and be the mediator between the adult world on behalf of her little sister.

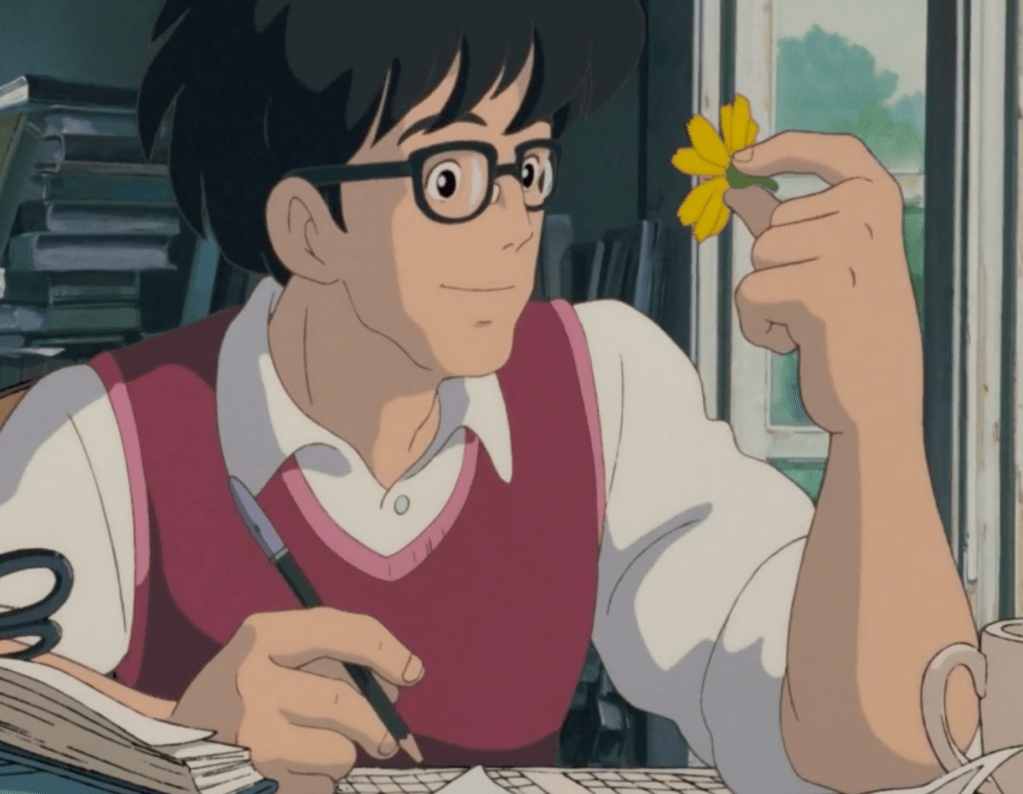

And perhaps most importantly, we do not see the idealized qualities of children completely lost in the adults in the film. The Granny is a keen advisor to the kids and the one that informs them about the spirits in the first place. And their father, despite the responsibilities of work and the heavy weight of an ill spouse, is so different from the fussy and grumpy Mr. Darling in Peter Pan.

Mei and Satsuki’s father embodies so much of what I hope to be for my kids because he seems able to retain some of these idealized qualities of childhood. He has a fun-loving and light-hearted spirit. He fosters curiosity and imagination. He retains a childlike sense of wonder and appreciation for nature.

One could say that Mei and Satsuki’s father bridges the gap between Neverland and the real world in a way that Peter Pan never could.

Citations

- William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up”

- Matthew 19:14

- J.M. Barrie, Peter Pan

Leave a comment