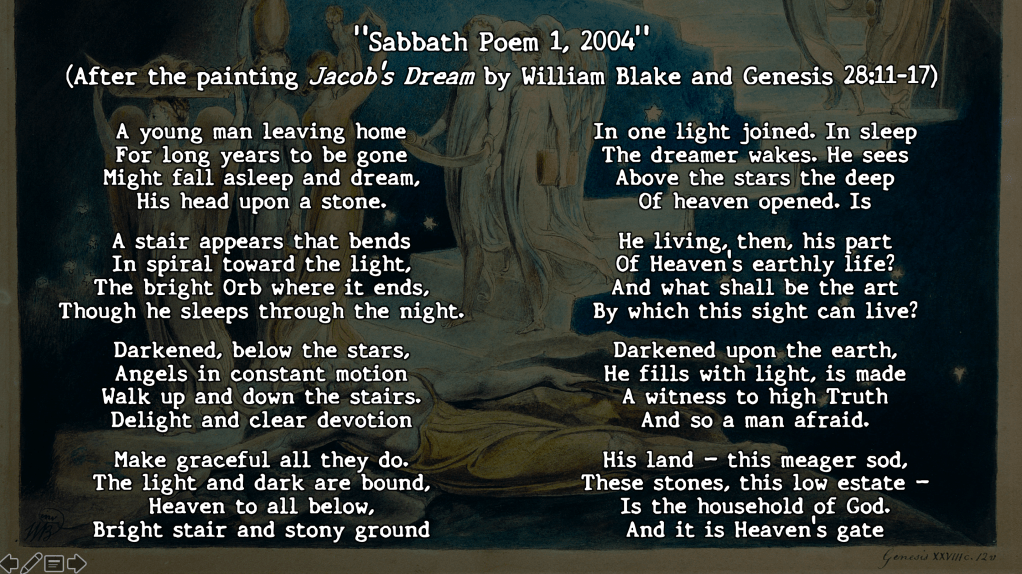

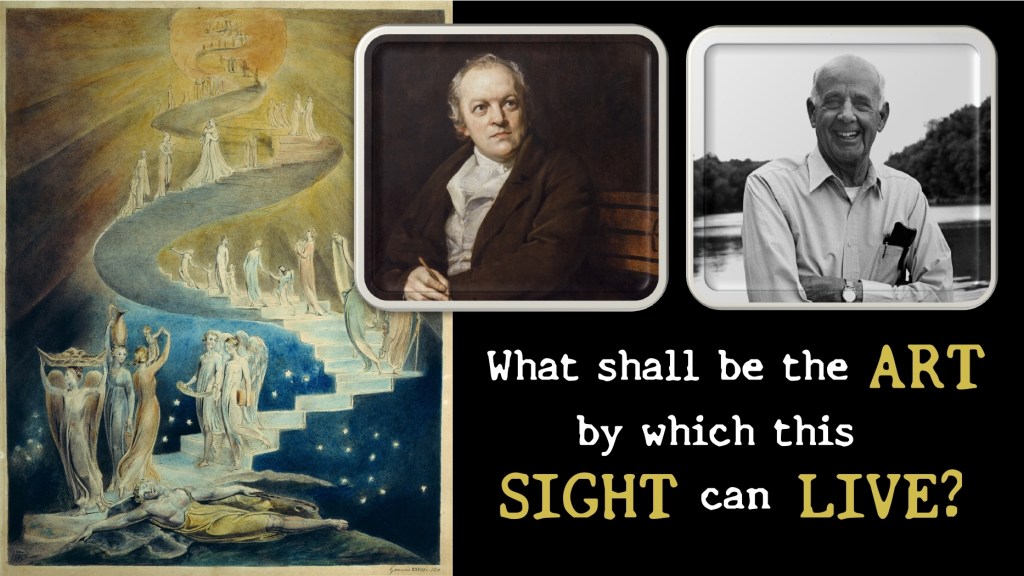

The poem I analyze in this video is a 2004 Sabbath poem written by Wendell Berry, who is my favorite writer of all time. Berry’s Sabbath poems are typically personal pieces of meditation, inspired by his time outdoors. But this one is a bit different. He claims to have drawn inspiration from a painting by the English Romantic-era poet and artist William Blake, which depicts the story of Jacob’s Ladder from Genesis. In this famous Biblical passage, the Israelite Patriarch Jacob dreams of a stairway connecting heaven to earth, leading him to name the place where he slept Bethel, or the house of God.

What impresses me most about this poem is how Berry is able to pay homage to this painting and passage of scripture, while synthesizing ideas from both, in order to communicate something new and, in my opinion, extremely inspiring.

The poem begins like this:

“A young man leaving home

For long years to be gone

Might fall asleep and dream,

His head upon a stone.”1.

In this first stanza, it’s clear that Berry is not merely discussing the particulars of Jacob’s story. His dreamer is anonymous, and there is obviously something of a universal experience being hinted at here.

It’s also key that this man is described, like Jacob, to be on a journey away from his home. The concept of home and the theme of homecoming is present across much of Berry’s work. To come home, in a metaphorical sense, is to arrive at a place of secured identity, purpose, and well being. But to be at home for Berry also means a commitment to community and culture and place. So, this man, reminiscent of the Biblical prodigal son, is both literally and figuratively far from his home.

From here, Berry describes the dream:

“A stair appears that bends

In spiral toward the light,

The bright Orb where it ends,

Though he sleeps through the night.

Darkened, below the stars,

Angels in constant motion

Walk up and down the stairs.

Delight and clear devotion

Make graceful all they do.

The light and dark are bound,

Heaven to all below,

Bright stair and stony ground

In one light joined.”

What becomes clear in both the poem and the painting is the seamlessness by which heaven and earth are connected, which the man had apparently failed to notice before. This speaks, I think, to a core ideal of both Blake and Berry — a distaste for dualism. For starkly dividing earth and heaven, soul and body — for demonizing the physical and elevating the spiritual.

We see this message across many works by William Blake, in which he celebrates the physical life and the body, as well as the transcendent. In a poem written to some dear friends – which many actually link to this painting – he wrote of a vision of Jacob’s ladder that featured his friends upon the steps.2. Heaven and earth, it seemed to Blake, are not so far apart.

Wendell Berry feels this way as well. In an essay, he called this kind of dualism that separates the spiritual and physical “the most destructive disease that afflicts us.”3. He often urges his readers to view the physical world — the earth, our communities, our work — with a sense of sacredness.

The poem puts it so well. The light of heaven and the darkness of earth are bound together. The physical and spiritual are united by the “one light” of God.

Then suddenly,

“…In sleep

The dreamer wakes. He sees

Above the stars the deep

Of heaven opened.”

Upon the revelation of the nearness of heaven and earth, he reflects,

“…Is

He living, then, his part

Of Heaven’s earthly life?

And what shall be the art

By which this sight can live?

Darkened upon the earth

He fills with light, is made

A witness to high Truth

And so a man afraid”

This man, like Jacob, is awed and humble by his dream. He is filled with the light of God. He feels urgency at the gravity and meaning this “high Truth” of the nearness of heaven imparts to his daily, earthly tasks. He wonders what his “art” should be, that would allow this “sight” to “live.” In other words, what practical actions should he take, how should he approach his life and work, in order to manifest this reality that the physical world is imbued with the divinity of heaven?

These are questions, I think, that should strike at the hearts of all of us who hold similar ideals. If we believe that there is a sacred quality to this world and our actions in it, if we believe that we get to experience or even participate in the light of heaven breaking into our earthly realm, then we should be convicted and humbled by the sense of purpose and responsibility this implies.

In Genesis, when Jacob awoke from his vision, he regarded the place he slept as holy. “Surely the Lord is in this place;” Jacob said, “and I knew it not” (Genesis 28:16b) Berry takes this ancient story, and through his poem’s narrative, universalizes Jacob’s experience. The poem ends with this man, likely a farmer as it turns out, summarizing his newfound vision using some of Jacob’s exact wording:

“His land – this meager sod,

These stones, this low estate –

Is the household of God.

And it is Heaven’s gate.”

While this man was “far from home” before he slept, he has now returned home in a profoundly spiritual and physical sense. He walks away from this revelation with a renewed sense of purpose, identity, and connection to his place.

It’s safe to say that Wendell Berry urges us all, whether or not we are farmers, to view the natural world in such a way. But he looks to this painting and this scripture passage in order to say something even more universal. What should be our response, as we consider the sacredness of the earth, our work, and our daily lives? “What shall be the art by which this sight can live?”

Citations

- Wendell Berry, “Sabbath Poem 1, 2004 (After the painting Jacob’s Dream by William Blake and Genesis 28:11-17)” in This Day: Collected & New Sabbath Poems – https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/17572972-this-day

- William Blake, “To my dear Friend Mrs Anna Flaxman” – https://www.bartleby.com/235/143.html

- Wendell Berry, “Christianity and the Survival of Creation” in Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community: Eight Essays – https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/146150.Sex_Economy_Freedom_and_Community

Leave a comment