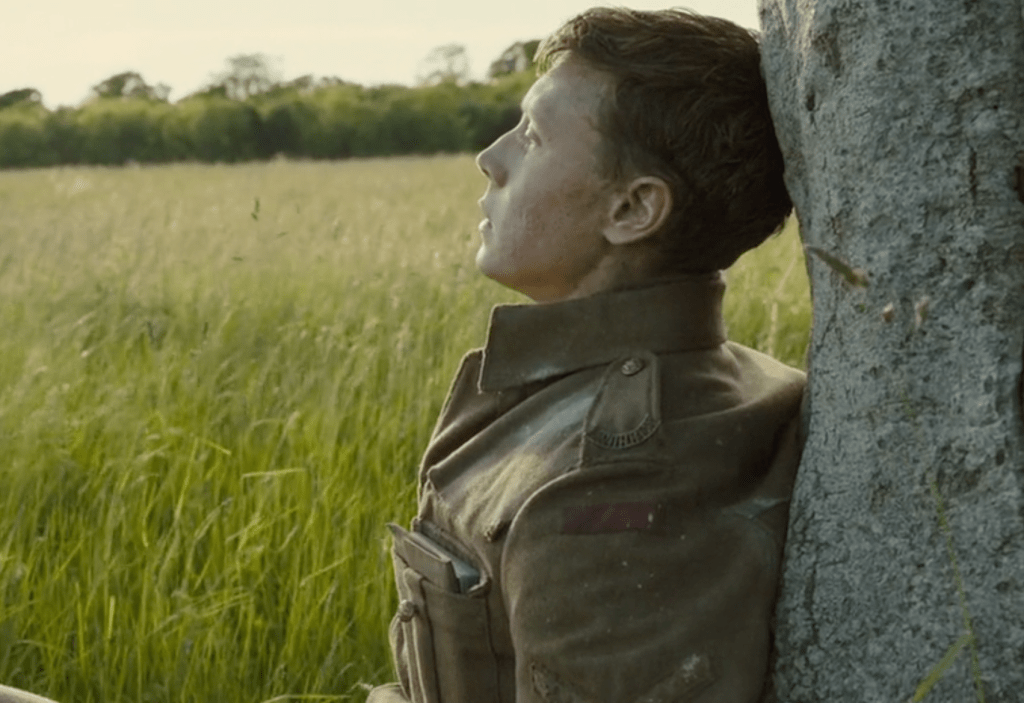

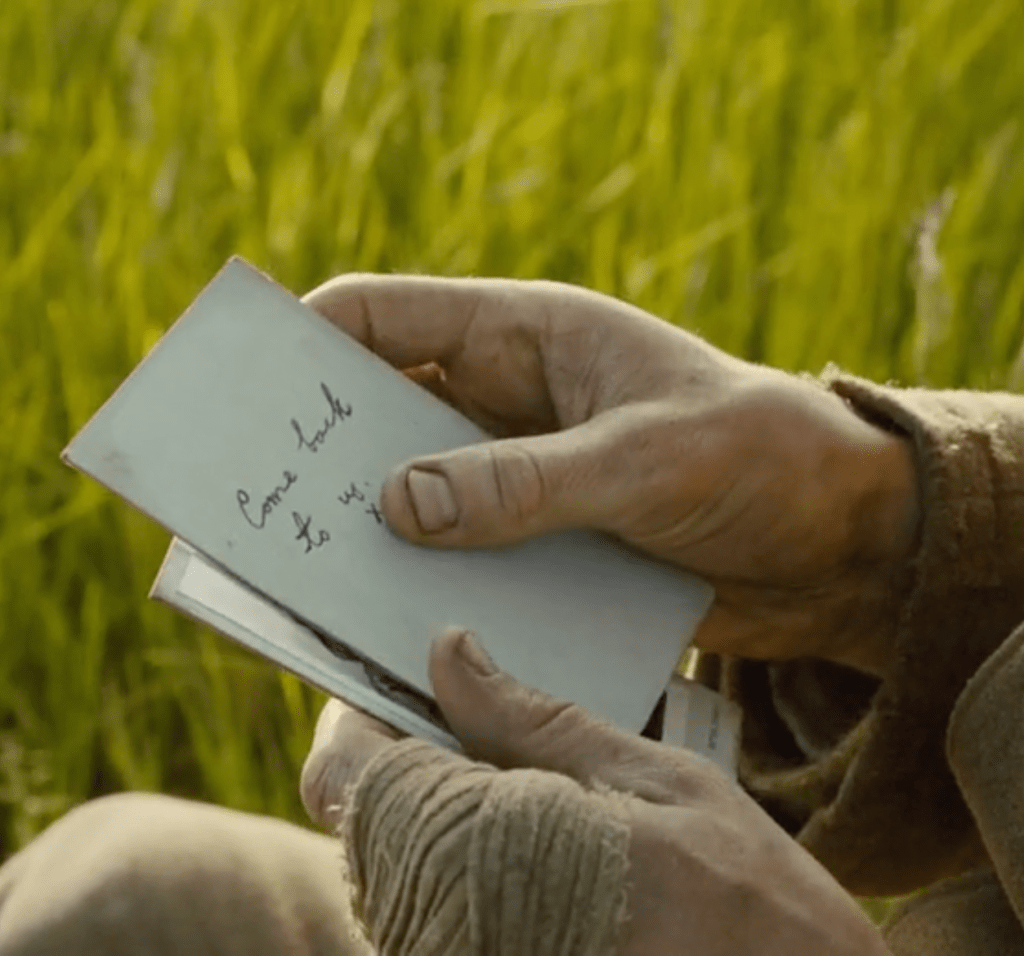

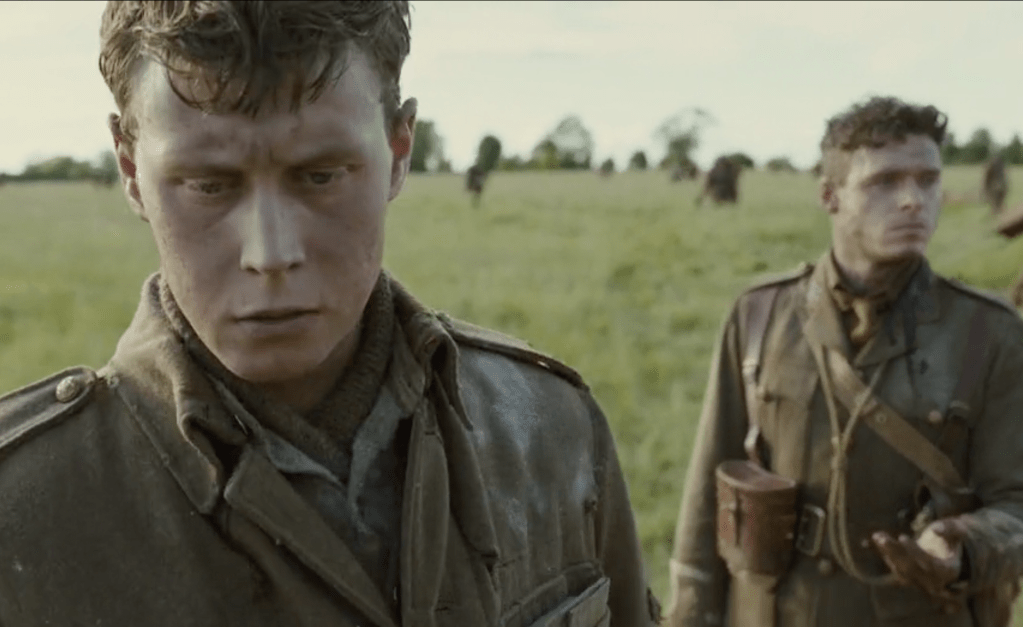

Some have accused director Sam Mendez of ending his epic WWI film 1917 in a way that overly exalts individual heroism and glosses over the horrors of the war. But I think the film’s final scene is deceptively complex. On the surface, it may seem like a happy ending. Lance Corporal William Schofield has completed his mission and survived his trials, against all odds. He cradles the photo of his family, as the hopeful sunrise shines brightly on his face.

But as we see his wife’s scrawled note on the back of the photograph, “come back to us,” I couldn’t help wondering, after the harrowing two hours of this film. Can Will Schofield ever fully “go back” to his family? Is truly “coming back” — to his home, or even to himself — fully possible after what he has endured?

This sense of ambiguity pervades the entire film. And this is a perfect approach to take, considering the overall moral obscurity of war and the complexity of World War 1 in particular. As I watched 1917, I couldn’t help recalling another story, which I’ve taught before: Tim O’Brien’s classic Vietnam War novel, The Things They Carried. In his proposed mission to tell a war story that is as “true” as possible, O’Brien asks,

How do you generalize? War is hell, but that’s not the half of it, because war is also mystery and terror and adventure and courage and discovery and holiness and pity and despair and longing and love. War is nasty; war is fun. War is thrilling; war is drudgery. War makes you a man; war makes you dead.

Part 1 – Contrast and Paradox

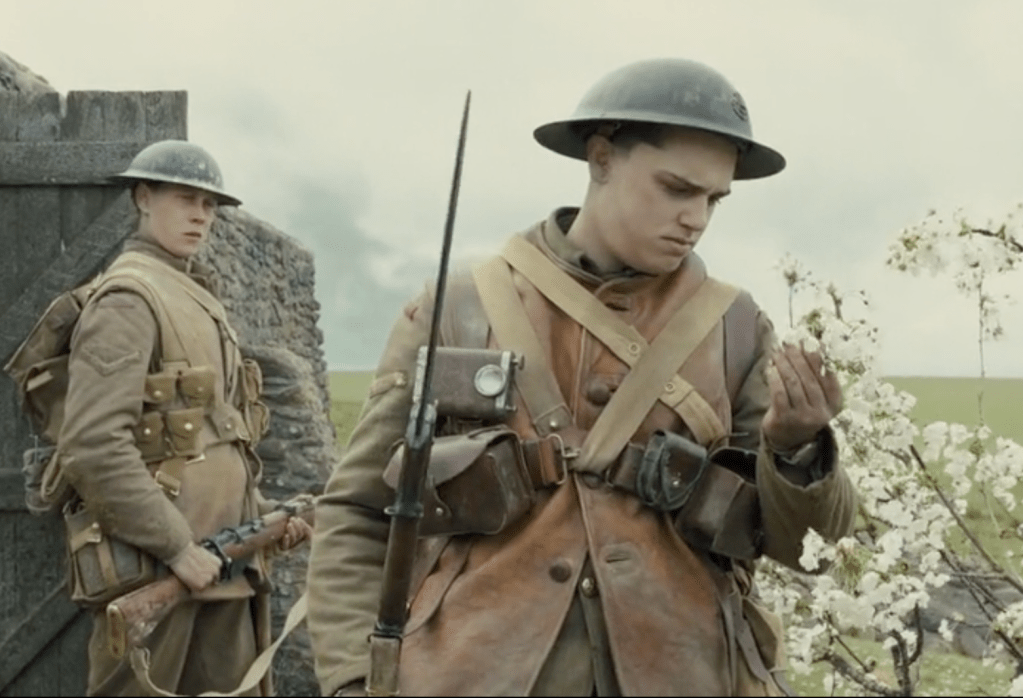

In the first half of 1917, we see many paradoxical moments, all of which illustrate the way that the war defies generalization. Yes, the pace and suspense engage us, but Mendes also draws us in by constantly undercutting our expectations and contrasting beauty and goodness with horror and evil.

Once Schofield and Blake make their way to the underground barracks, there is a reprieve of momentary humor involving a rat. Then suddenly, the moment is disrupted by the jarring explosion the rat trips. The brotherhood and care displayed by Blake and Schofield are continually contrasted with the death and decay around them. The cherry trees the pair passes are clear images of life, beauty, and fruitfulness. But they have been disfigured by violence. They come upon numerous pastoral images — grazing cattle, a picturques farmhouse — which are also marred by the destructive technology of the war. And finally, the courageous and honor-driven Blake (who we assumed to be the protagonist up to this point) shows an uncanny sense of humanity in their first confrontation with an enemy soldier. Yet as he attempts to help the German pilot, he is killed in an absurd, unceremonious fashion. Confusion and ambiguity abound.

Part 2 – Inverted Archetypal Symbolism

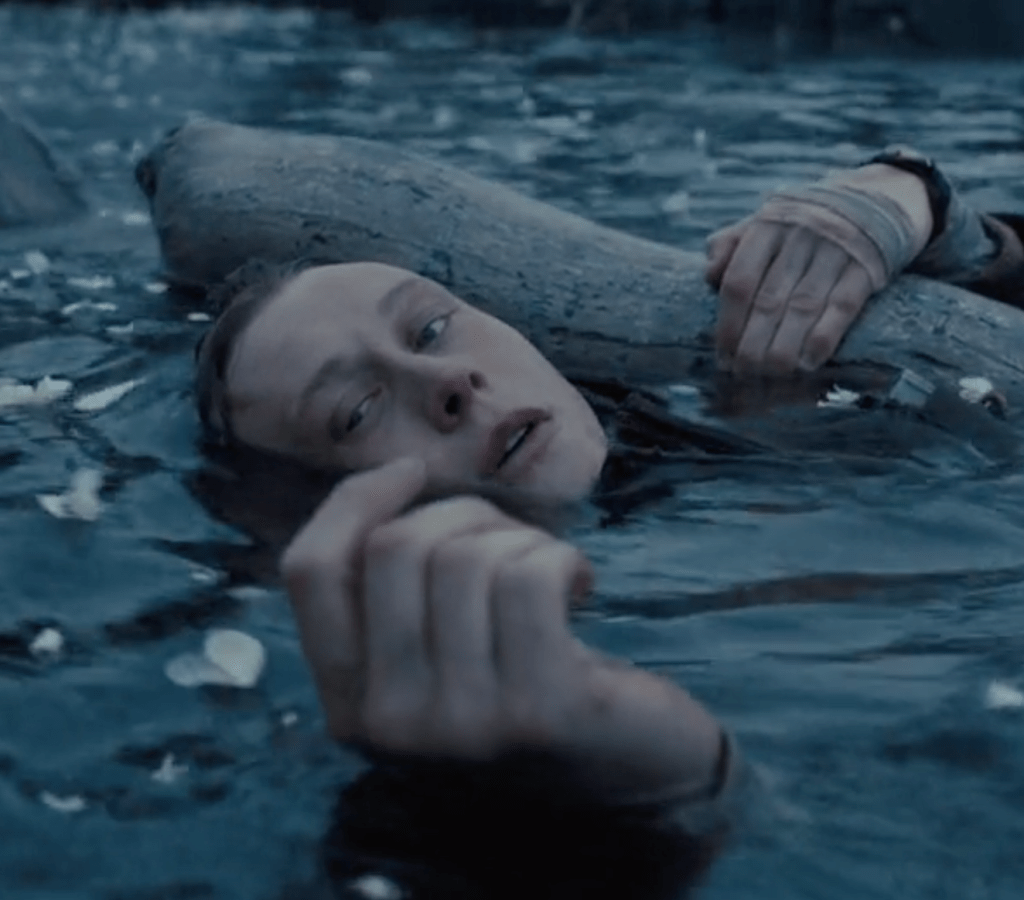

This subversion of expectations continues when Schofield arrives in the village and awakes after being knocked unconscious. Here, the film’s imagery is rife with archetypal symbolism. Think of the patterns of the Bible or great epics like Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Schofield begins, like Dante, in complete darkness, then proceeds into a hell-like landscape. He quickly descends to what seems like the lowest point in the town, only to be reborn and seemingly baptized in the river.

In such patterns, a hero’s descent into the abyss and subsequent rebirth are typically followed by a consummation of the hero’s hopes — like Dante beholding God at the peak of his ascent or Odysseus’ return home. Likewise, we see Schofield ascend up a mountainside after his baptism, ending with a redemptive scene of a long-lost paradise, as soldiers are uplifted by the strains of a gospel song, promising hope and eternal rest to weary warfaring strangers.

But yet again, we see ambiguity disrupting these familiar patterns. At the bottom of Schofield’s descent, he does not find evil in the dark abyss. He finds instead the film’s most potent images of innocence: a cooing baby and a nurturing mother figure, reminiscent perhaps of the Biblical Mary. Then immediately after leaving this seemingly divine encounter, Schofield is thrust again into absurdity, as he chokes an unsuspecting, nameless soldier in a scene of animalistic violence. And in the film’s final act, after Schofield’s ascent and possible consummation of hope, he is suddenly forced to descend once again into uncertainty and violence. And as he attains what we assume to be his personal triumph, he is told, “Hope is a dangerous thing.”

Part 3 – Homecoming

As I said before, the film’s ending also captures well this realistic look at war’s defiance of generalization. It revisits the serene image of a tree, symbolically signaling yet another cycle of a “new beginning.” Mimics the calm tone from the opening scene, we can’t help feeling jarred. We can’t help questioning this sudden shift to a seemingly peaceful image. Is this really a new beginning for him? It’s hard to finish this film with a true sense of hope, after having endured two hours of suspense and brutality. And it is Schofield himself, after all, who scorns the idea of returning home at the beginning of the film.

Additionally, if we view the home or a house as a symbol for one’s self, an anchor to one’s identity, there are more questions than answers. Will he ever recover from the trauma he has faced? Is returning home a hopeful thought, or will it only bring further suffering? It’s hard to say, considering that he already said it’s better not to return. According to the general, such hope can be a dangerous thing. This theme and this ending certainly DO not suggest that war is simply a heroic endeavor.

Conclusion

Tim O’Brien wrote,

War is hell. As a moral declaration the old truism seems perfectly true, and yet because it abstracts, because it generalizes, I can’t believe it with my stomach. Nothing turns inside. It comes down to gut instinct. A true war story, if truly told, makes the stomach believe.

As many have said, the film presents a harrowing, realistic portrait of war, which transcends easy generalizations, ideological and political agendas, and even its own historical backdrop. Its story, score, camera work, and imagery all work to this end. We believe it. We believe it on a human level. In Tim O’Brien’s words, we believe it in our stomachs.

Leave a reply to onoe97 Cancel reply